Serendipity is an odd thing. It’s as if the future is written all around us on little post-it notes, but we never read them until an event unfolds and we suddenly realize that, just maybe, we might have seen it coming.

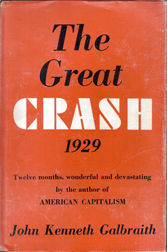

A few years ago my best friend’s dad gave me an amazing collection of thousands of books. I’m a writer, my wife’s a librarian, we were like kids in a candy store. It’s taken years to process the books, and we still have 20 boxes in my garage. So a couple of months ago I was down in the garage sorting a stack of books and one book stood out. Because of its cover. Because of its author. Because of its simple title: The Great Crash. 1929.

John Kenneth Galbraith, the influential popular economist, wrote the book in 1954 as “an economic history of the lead-up to the Wall Street crash of 1929”. Given all the concern over the past year about the mortgage crisis, it seemed like a timely topic, so I put it on a short stack to read. I finally got down to reading the book on a trip back east and literally just finished reading it last Friday. That was the day the “extraordinary weekend” started before the 504-point crash on Monday. It’s an understatement to say that I felt like I had just read the history of what is about to unfold before us.

John Kenneth Galbraith, the influential popular economist, wrote the book in 1954 as “an economic history of the lead-up to the Wall Street crash of 1929”. Given all the concern over the past year about the mortgage crisis, it seemed like a timely topic, so I put it on a short stack to read. I finally got down to reading the book on a trip back east and literally just finished reading it last Friday. That was the day the “extraordinary weekend” started before the 504-point crash on Monday. It’s an understatement to say that I felt like I had just read the history of what is about to unfold before us.

Without overstating the parallels between 1929 and 2008–the mechanisms behind the collapse are undoubtedly different–the pattern is hauntingly familiar, right down to the constant stream of assurances from vaunted economists and elected politicians that “we’ve now seen the worst of it”, “a turn around is just around the corner” and, my personal favorite, “the fundamentals of our economy are still strong”. This is what Galbraith called the collective belief in the power of incantation. I’ll let others argue about the economic comparisons of 1929 to 2008, but the human factor–the wholesale denial of destruction even while it’s underway–is breathtakingly familiar.

I hate to be the alarm clock if you’ve been oversleeping, but it’s time to wake up and get it together. We’re in for a rough ride, and it’s not going to be pretty–especially for marketers. I’ve spent the past year pouring all of my resources into a marketing technology startup. It’s a scary time to look up and realize you’re standing on a small rock in the middle of a raging sea and a gathering storm. But it’s even worse to keep your head down and spout incantations about how it’s all going to turn around real soon now. So here’s my blog-condensed playbook of what lies ahead.

It’s going to get a lot worse before it even starts to get better. We’re only seeing the beginning throes of chaos in our financial system. We’ll see liquidation panic play out over days and probably weeks. The government will make various attempts to stop the bleeding, but eventually they’ll be left to do nothing but call impressive meetings of Very Important People who deliver more incantations. The impact on available cash and credit will force companies to cut spending deeply. Jobs will be lost on a large scale, and just like past recessions, marketers will be heavily over-represented in the RIFs. At many companies, marketing executives and managers will be released and become freelance consultants, marketing associates and directors will take over and run marketing operations primarily as sales support. Lead generation will of course lead everything.

That’s the bad news. And make no mistake, it will be ugly. The good news is, chaotic disruption is a huge opportunity for innovation, though it’s not for the faint hearted. In any system, change can only be accomplished by disruption and reorganization. Instead of looking at the disaster ahead as wholesale destruction, look for the patterns of reorganization–and find the companies that have the intelligence and bravery to share your world view. Look for the opportunities to solve problems and help companies grow when others are running scared. Proctor and Gamble, Kellogg and Chevrolet were companies that invested in advertising during the Great Depression while the vast majority of companies cowered in their caves, and during the worst financial meltdown of our history (so far anyway) they managed to grow and build a sizeable lead over competitors leading into the recovery.

Who are the companies that will be investing in growth as the financial system crashes around them? And what will they be investing in? I know where I’m placing my bets. While much of the Web 2.0 hype will be silenced in the coming months, I’m betting people will go online to connect with peers more than ever before. To share their fears, to relate, to vet anything that anyone is telling them about what’s happening, and most of all, to find opportunities. I’m also betting that the decks will be cleared for a new generation of marketing tools and marketing personnel for whom social media and community isn’t a trend, but a given. This is the transition point.

Seriously. It’s time to wake up. There’s a rough road ahead. Buckle your seat belt and grab the wheel.